As Easter looms on the holiday horizon, my thoughts have turned to history’s greatest meeting point of religion and humor: Monty Python’s Life of Brian. But as I looked at the movie, and the controversy around it, I came to a startling realization.

Life of Brian can teach us how to live.

Unfortunately, a lot of the controversy around the film’s original release overshadowed its message. Because, unlike most Python movies, or most great comedies, it does have a message.

First, a caveat. I’m not in any way here to disparage the actual Gospels, Psalms, Shewings of Julian of Norwich, Ramayana, Hadith, or Deuteronomy, simply to point out a couple of valuable morals hidden within one of the greatest comedies of all time.

A Brief Historical Interlude

I assume, if you’re on this site, that you know plenty about Monty Python, but I will give you an incredibly quick recap in case you need it. Life of Brian was the Python’s third film. Their second film, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, was a huge hit. (Like, an enormous hit, and an incredibly important cultural moment, which always feels weird to me since I grew up later with Monty Python as a cult thing that nerds quoted instead of having actual conversations with each other.) The Pythons went on a world tour to promote Holy Grail, and at some point during a layover at an airport someone asked what their next project should be. Eric Idle said: “Jesus Christ: Lust for Glory”—either to the other Pythons or to the press, and after they stopped laughing they thought about it and decided to go ahead with it.

Life of Brian follows Brian, an unassuming young man growing up in 1st Century Judea, who tries to join an anti-Roman movement before accidentally becoming a messianic figure. After months of research they created what may be the single most accurate film about the 1st Century C.E. It leaves both The Last Temptation of Christ and The Passion of the Christ in the dust (which it promptly shakes it from its feet as it leaves town)—from the tense relationship with the Romans to the proliferation of philosophers and self-proclaimed messiahs to the fractured ideas of how to oppose occupation. The Pythons decided that Jesus himself was not really a good target for satire (they all liked his teachings too much) but the structures of religion were fair game, as were the various political factions that had sprung up and could mirror the ever-more-ridiculous splinter groups of the 1960s.

A Note On Jesus

Life of Brian is really explicitly not about Jesus. That gentleman does have two cameos, and the film is completely, almost weirdly reverent during each of them. I say weirdly because “reverence” isn’t a word that comes up much when discussing the Pythons. First, it’s made quite clear that the stable down the street from Brian’s—you know, the one with Jesus in it—is bathed in holy light, surrounded by angels and adoring shepherds, the whole shmear. The second cameo comes when Brian attends The Sermon on the Mount. Not only is the Sermon well-attended, but everyone approves of the few snatches of the speech they’re able to hear. He’s also referred to as a “bloody do-gooder” by a former leper who lost his revenue stream when Jesus healed him. If you somehow only learned about Jesus from Brian, you’d have an image of an objectively divine person who was a hugely popular public speaker, and who could actually heal people. This is a more orthodox version of Jesus than the one presented in Last Temptation.

Predictably, however, the film caused a firestorm of controversy when it came out.

The Pythons vs. the World

EMI, the film’s original producer, pulled out about two days before the Pythons were set to go to Tunisia to begin filming. Eric Idle mentioned this disaster to his friend George Harrison, who mortgaged his house to found Handmade Films, which would later produce such British classics as Mona Lisa, Withnail and I, and Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. They decided to premiere it in America first (give yourself few minutes to laugh at the idea of America welcoming a religious satire with open arms) because, well, we have freedom of speech enshrined in the Constitution. What they didn’t expect was that, first, they had to make out wills before they came to New York just in case someone took a shot at them, and second, the people who protested the most vociferously were The New York Association of Rabbis, who were angry at the use of a prayer shawl in the stoning scene (seen above).

It’s worth noting that the film caused its own miracle, because members of different stripes of Judaism, Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and Protestantism all came together to picket film screenings. Despite Life of Brian being banned in some areas of the Bible Belt, the film ultimately benefited from the controversy, opening on 600 screens across the U.S. instead of the original 200, and earning more than expected.

The reason the Pythons were seriously worried comes down to a single person: Mary Whitehouse. She was a teacher who, during the 1950s, became obsessed with the idea that Britain’s moral character was failing, and that the only way to help was to send piles and piles of letters to the BBC to tell them not to allow people to use the word “bloody” on air. She developed two large groups, the “Clean Up TV Campaign,” which became the National Viewers’ And Listeners’ Association, and the Nationwide Festival of Light, which managed to wield some influence with high-level politicians, who in turn pressured the executives at the BBC to listen to her demands. Amongst these demands were: less war footage shown on TV, lest the British public become too pacifistic, less sex in general (surprise), and… less violence on Doctor Who?

Wait, Doctor Who?

Huh. Yes, she was angry about the “strangulation—by hand, by claw, by obscene vegetable matter” in “The Seeds of Doom.”

Noted.

Buy the Book

A Prayer for the Crown-Shy

Whitehouse’s highest profile success came just two years before Brian’s premiere, when she sued the publishers of Gay News (exactly what it sounds like) over a poem called “The Love That Dares To Speak its Name.” The poem, a play on the phrase ‘the love that dare not speak its name’ from Oscar Wilde’s boyfriend’s poem “Two Loves,” upped the homoerotic stakes by centering on a Centurion who has pretty unholy feelings for Jesus. Whitehouse later told a reporter that “I simply had to protect Our Lord.” The specific thing they sued for was “blasphemous libel” (also exactly what it sounds like) and, in a trial where the prosecuting attorney told the court: “It may be said that this is a love poem—it is not, it is a poem about buggery,” and which only allowed two character witnesses for the defense rather than any experts on pornography or theology, the jury found for Whitehouse (10-2!) and Gay News was fined £1,000, while publisher Denis Lemon was fined £500 and received a nine-month suspended prison sentence. This was for a crime that had not been prosecuted since 1922.

So when someone in Brian’s crew leaked 16 pages of the script to the Festival of Light, the Pythons became considerably more nervous about their movie.

At first the group only encouraged Christians to pray for the failure of the film, but that soon turned into the usual letter writing campaigns and pressure on local councils. The Pythons decided to get out ahead of any backlash by agreeing to a televised debate with two prominent Christians on the chat show Friday Night, Saturday Morning.

The debate (embedded below) manages to be more painful than you might reasonably expect, and I urge everyone to watch it. Historically speaking, it’s an extraordinary document of a cultural moment that could have only happened in the 1970s. A pair of young-ish satirists speak earnestly about their intentions for the movie, telling the interviewer that, after devoting themselves to studying the Gospels, they all came to the conclusion that they couldn’t make fun of Jesus. It’s heartbreakingly sweet, given what comes next: Mervyn Stockwood, then Bishop of Southwark, clad in purple robes and fondling the largest crucifix I’ve ever seen anyone wear (and my great-aunt was an old-school nun) and Malcolm Muggeridge, a former editor of Punch who converted to Christianity in his late 60s—after a life of public debauchery (and who, along with Mary Whitehouse and a pair of British missionaries, was a cofounder of the Festival of Light)—proceed to badger and heckle the two Pythons, talking over them, insulting them, and refusing to engage in any true debate beyond wagging their fingers, while their moderator, Jesus Christ Superstar lyricist Tim Rice, sits back and watches rather than adding any points from his own experience working on a theologically thorny project.

The two older men vacillate wildly between mugging for the audience and talking over Cleese and Palin in horrifyingly condescending tones. It isn’t a debate, because the Bishop and Muggeridge aren’t listening, they’re simply pontificating on the state of the world and treating their opponents like naughty schoolboys who need to have their knuckles rapped (I’ll remind you that Cleese and Palin were pushing 40 at this point).¹ The Pythons did manage to get some excellent points in, with Cleese saying, “Four hundred years ago, we would have been burnt for this film. Now, I’m suggesting that we’ve made an advance”—but it became clear that the two Christian leaders were not there for either the five-minute argument, nor the full half-hour—they were just there to berate the Pythons.

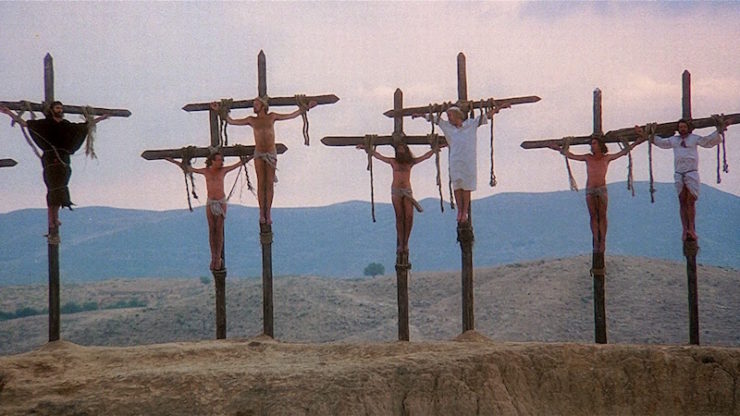

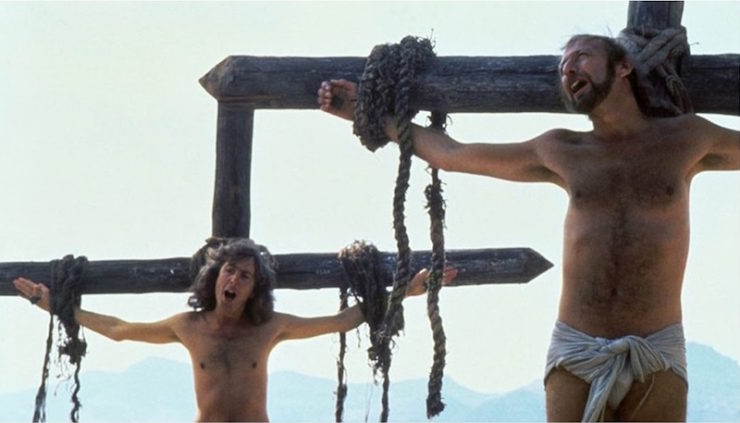

The men’s biggest concern was with the ending–the musical chorus line that happens during Brian’s crucifixion. (Can I admit something? Just typing that line made me grin uncontrollably. Perhaps I’m not the best person to write about this, maybe my position is already too clear.) When I re-watched the debate and documentary for this post, I was reminded that both of them are really hung up on the crucifixion. They keep returning to that moment above all others in the film, with Muggeridge in particular expressing outrage that anyone could make a joke out of moment that has inspired the greatest works of Western art in the last 2,000 years. Stockwood further asks, “Why lampoon death? That sort of worried me. I don’t think one would make a farce about Auschwitz or of death … it was a shattering thing what happened to [Jesus]–crucifixion.”

Which, hm. First, what the Pythons are doing in their crucifixion scene is stripping the uniqueness from Brian.

He’s the one we’ve followed through the story, so even if he isn’t the Messiah, we’re still on his side, empathizing with him, rooting for him, so that when he’s captured and sentenced to crucifixion it’s legitimately terrible, but the way the Pythons deal with it is to show us a long line of condemned people all being processed with ruthless efficiency by Romans. It shows crucifixion as it most likely actually was: just another day in the Roman machine, exacting obedience through public torture. I have to wonder if that’s part of what the two men are objecting to. Because generally in the West, when you think of crucifixion there’s really only one Guy who comes to mind. Even when Kubrick made Spartacus, about a Roman pagan who was crucified about 40 years before Jesus’ most likely birthdate, he plays with imagery that was used in Christian art to evoke a sense of holy martyrdom around his character. (The “I am Spartacus” line is also played with in Life of Brian.) It became so iconic a part of Jesus’ story that according to Catholic lore, Peter specifically asked to be crucified upside down so as to not exactly replicate his Master’s execution.

So for Life of Brian to take that moment and turn it into a song-and-dance number isn’t just the usual Python silliness, but something much deeper… but I’ll come back to it in a minute.

The debate finally came to an end with the Bishop and Muggeridge shouting down all of the Pythons’ points. Tim Rice thanked the men for their time, but the Bishop managed to get the last word by snapping, “You’ll get your thirty pieces of silver, I’m quite sure,” while Rice murmured, “I hope that the film won’t shake anybody’s faith.” Then, in what is possibly the most whiplash-inducing moment of the decade, Rice cut to Paul Jones performing “Boom Boom (Out Go the Lights)” in which the singer announces his intent to stalk his ex-girlfriend and beat her into unconsciousness as soon as he finds her. Neither religious leader—still onstage for the performance—saw fit to decry this celebration of violence in the media. Not “shattering” enough, presumably.

A Brief History of Jesus on Film

Life of Brian was coming out of a very specific social milieu that has since shifted in ways that would make the film impossible to make now. In order to get that, allow me to give you an EXTREMELY abbreviated history of The Jesus Movie:

In the beginning was spectacle. The Silent era produced a couple of brief films of the Nativity, and some giant Cecil B. DeMille epics. In the fifties, we got Greatest Story Ever Told and King of Kings, both huge films with casts of thousands that used a syncretic approach to the New Testament. By cherry-picking some of the most famous scenes and quotes from each of the Gospels, and shoving them all into one film, they try to give you an idea of Jesus’ life, and an extremely sanitized retelling of the beginnings of Christianity. In the 1960s we got a stellar Jesus movie, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Gospel According to St. Matthew, which does exactly what it says on the tin – the words and events of Matthew are depicted in black and white via a very tight, constantly moving shot. This film, with its minimalism and aggressively revolutionary Jesus, is often seen as a reaction to the big budget spectacles of Hollywood.

The 1970s created a perfect storm of liberalism, social awareness, musical theater, and the Jesus Freak movement, giving us Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar, both of which were adapted into films in 1973. (Full disclosure: I am inordinately fond of both of these films.) JCS features a long-haired hippie Jesus, Black revolutionary Judas (who’s actually kind of the hero), and Native American Earth-mama Magdalene (who’s a main character rather than a hanger-on.) They sing, at length, about revolutionary movements, selling out, and megalomania. In Godspell we get a colorful troupe of hippies running amok in Manhattan and acting out a stripped-down version of Matthew and Luke like an evangelical Sesame Street gang. (Victor Garber, in a nod to the Christianization of the Jewish historical Jesus, wears a skintight Superman t-shirt throughout the film.) And even Franco Zeffirelli’s far more traditional Jesus of Nazareth (the one that used to get shown on TV at Easter each year) features a complicated, politically-motivated Judas.

In 1979, as people were becoming increasingly disillusioned with most of the revolutionary movements, Life of Brian arrives, able to use the Jesus story as a jumping-off point for their character Brian, and a wide-ranging satire that mocks organized religion, political movements, and Latin teachers with equal glee. Hilariously (?) Martin Scorsese ran into even more controversy, death threats, and low earnings when he made The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)—which, again, is based on a novel by Nikos Kazantzakis and at no point claims to be any kind of canonical gospel—while Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004) was released to praise from religious groups and boffo box office, despite drawing on the Book of Revelation, traditional Passion art, and, most notably, The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ, a book describing the visions of 18th century nun Anne Catherine Emmerich, rather than sticking to Gospel-era canon.

But What About the New Testament?

So glad you asked. Talking about what sort of life the gospels want you to lead is fairly difficult. Since there are four of them, and they all have slightly different takes on the teachings that evolved into early Christianity, it can get overwhelming.

Here’s my best attempt:

- Mark = put all of your moral affairs in order, as the end is nigh.

- Matthew = are you poor, but good? Wretched, blighted, suffering, oppressed, but trying your best every day to be decent person? You’re probably going to be okay, kid. Wait, you want me to tell you how? I’m not going to tell you how, that would be cheating.

- Luke = the same as above, but with slightly more flowery language.

- John = put all your moral affairs in order – oh, neat, a miracle! Now keep putting them in order, because the end? Super nigh.

Depending on which gospel you’re reading, you’re supposed to be meek, compassionate, or radically empathetic—like, Betazoid level empathetic. In Matthew, you’re told to be perfect; throughout Mark, you’re told that there were people living then who would see “the kingdom of God come with power,” and in Luke that even the most prodigal of sons would be forgiven.

If you’ll allow me to delicately sidestep the non-canonical stuff because it would take too long, I’ll make my first point: even if you’re trying to align your life with those gospels (or with the more formal teaching of Catholicism, Orthodoxy, or most Protestantisms) Life of Brian actually adds an exciting addendum to those teachings. Because what is the true message of Brian? Be an individual. Be creative, think for yourself, don’t blindly follow people who claim to be in power—for won’t you both fall into the pit?

And above all, don’t be afraid to laugh at authority, especially when its name is Biggus Dickus.

Face the Curtain with a Bow

So, we must come, inevitably, to death. As I said, this seemed to be the sticking point for much of the controversy in the 1970s – far more than any lampooning of the origins of Christianity, it seemed to be the fact that anyone made a joke about crucifixion that was the issue.

Here’s why it’s important. At a certain point in an interview, Palin says that if they focused on the pain and torture of crucifixion it would have ruined the film, because making light of suffering wouldn’t work. But. They do give us the close-up of Graham Chapman’s face, in pain. They give us his hope when the Crack Suicide Squad shows up, and then how crushed and defeated he is when they just stab themselves. They do give us the moment of Mandy and Judith visiting him, and his utter desolation as they leave him. Is it the physical torture of Mel Gibson’s Jesus Chainsaw Massacre? No. Is it a hallucination of happiness that is then cruelly taken away, as in Last Temptation? No. It is a gradual breaking down of every scrap of hope that Brian has. Brian, who is not the Messiah (he’s a very naughty boy), who does not have a seat at Anyone’s right hand awaiting him. Brian, who, weirdly, expresses no religious beliefs of his own at all. Brian isn’t a grand historical figure, he’s just an everyday guy who wants to stand up to an oppressive regime. He could be anybody, he could be us, and we watch his life and hope be stripped away from him. And then Eric Idle leads him in a song. A death-defying, life-affirming, gleeful Fuck You of a song.

I still remember the first time I watched Holy Grail, but I don’t remember much of the first time I saw Life of Brian. What I remember of it is the ending. I remember watching that chorus line for the first time, and I remember feeling my mouth fall open as everyone began to sing. The idea that you could do that, that you could make something silly and joyful out of a tragedy—that tragedy, the axis mundi of the Western Canon—and just giggle. All bets are off if you can make fun of that. There are no limits to laughter, not even death. For me, this is the moment when Life of Brian joins that lineage of “greatest works of Western art.”

1. Interesting Side Notes: The televised debate between the Pythons and the Festival of Light was mocked to hilarious effect in a Not the Nine-O’Clock News sketch that aired a week later, ultimately asserting that Britain is a nation of Pythonists. You can watch the skit here. In 2014 the BBC revisited the controversy with a surprisingly emotionally-resonant biopic called Holy Flying Circus that highlights the Pythons as decent men men trying to helm a fight for free speech without losing their senses of humor. I recommend it to all the Pythonists reading this.

Leah Schnelbach asks themself at least once a day: “WWBD?” Come call them a blasphemer on Twitter!

Great essay, Leah. This is my favorite Python – so much brilliance.

Crowd: “We are all individuals.” One crowd member: “I’m not.”

I was just at a friend’s funeral, where she wanted pop songs played instead of hymns, which ended with “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.”

My kids are still a bit too young for this one (they love Holy Grail though), but they already know all the words to “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.”

The reason for this is that Iron Maiden has ended every one of their concerts for the past 4 decades or so by playing it after the encore as the lights go up.

Echoing something I read in the nineteen-eighties: this is the best Monty Python film because it’s the most coherent; every member is pulling in the same direction.

About that TV show with Muggeridge and the Bishop, Tim Rice (the host) had never done a chat show before and was out of his depth. An apocryphal story states that in the rehearsal Muggeridge and the Bishop had been polite if stern in their arguments. But when it came to the live broadcast the Bishop came in wearing full regalia which he had not done so in the rehearsal and he and Muggeridge completely changed their approach. They essentially ambushed the Pythons and the BBC. It is said that this breach of journalistic courtesy and good practice destroyed Malcolm Muggeridge’s career. Certainly very little was heard from him subsequently. But as I say, this is apocryphal.

Brilliant essay, thanks much.

I was 14 when this came out in the UK. I was brought up as a Catholic but had been developing my atheism since about the age of eleven.

I remember in church one Sunday the priest instructing the congregation not to watch this blasphemous film and it just really outraged me, I think that may have been the last time I set foot in a church other than weddings, funerals and to appreciate the architecture.

I agree with Bo Lindberg that this is the best Python film because it tells a single coherent story from beginning to end (Alien flyby notwithstanding). Sure there are digressions, but the plot continues to advance, unlike Holy Grail which is mostly a bunch of skits strung together.

What this article doesn’t cover is how accurately LoB portrays the middle east of the 70’s: splintered factions and terrorist groups.

I’m reluctant to watch that video, since people shouting over other people and not letting them speak is kind of an anxiety trigger for me, but it’s hard to reconcile the idea of anyone shouting down John Cleese with Cleese’s screen persona. I can see it with Palin, but you’d think Cleese would shout back and give as good as he got with some devastating putdown.

As for the film’s historical accuracy, I hadn’t realized it was that authentic, but I wonder about one thing. Shouldn’t the “Latin lesson” scene actually have been Greek? My understanding was that the Romans used Latin as the lingua franca and official language in the Western Empire and Greek in the Eastern one.That’s why the New Testament was originally written in Greek, and why Jesus’s epithet is Christ instead of Unctus or whatever the Latin equivalent would be. Or so I understand it.

@9: I haven’t watched the entire video yet since it’s over an hour long but from what I’ve seen this is not a shouting match like on Jerry Springer.

The “shouting over” is done in a civilized manner in the sense that there’s no yelling but the two religious “gentlemen” talk over the Pythons.

I don’t think that this would trigger you anxiety-wise; obviously, you be the judge, but I’d suggest you just have a look and skip to some spots in the debate in order to get a sense of the tone of the show.

@@@@@ 8 Not just the Middle East but a host of movements and hot spots and revolutionary/terrorist/wannabes etc throughout history.

Also, while the author could not possibly have cited every movie about Jesus, I was disappointed in the absence of Ben Hur, another DeMille-esque spectacle, sure, but one that also portrays a more manly version of the Christian redemption, (the Gospels as action movie) narrative based in the ideas of masculinity of the American Victorian Era when the book was written by retired Union General Lew Wallace. The story is not only a non-traditional take, but to a certain extent tells a very similar story as LoB, that of a man who lived contemporaneously with Jesus to provide context and a counter narrative to the traditional story.

Great essay, thank you! I saw LoB when it was released and have loved it ever since. I found it charming that a couple of decades later, my parish’s then-associate pastor could use the scene at the Sermon on the Mount as a reference in his own sermon. He loved LoB too.

@12 When I was a history teacher in the 90’s I frequently showed the “What has Rome ever done for us?” scene to open discussion of the Roman empire.

@9: I think you’re right about the Greek! But I’m guessing the Pythons had more experience reciting endless Latin lessons in school.

@11: I might do another draft and add Ben Hur – I want to talk more about The Robe and Quo Vadis?, too. Maybe I’ll do a director’s cut of this essay if I have a free weekend!

I was a senior in high school when this movie came out. I lived in the town now mostly known as Matt Gaetz home. The movie was highly anticipated by my social set, big Python fans all. Released on a Wednesday, I planned to see it Friday night, Wednesday being a school night. Local church leaders had already been agitating against the film before its release. Some of them apparently attended opening night and released a broadside against it in the local paper. A bomb threat prevented the showing Thursday night and on Friday the theater indicated they we pulling the movie. My later college roommate was one of the few people enthusiastic enough to go see it on the opening night, and made great reputation froM being able to describe the movie at parties

I’ve always felt that LoB also shows a great picture of the historical divisions among the Roman-occupied Jews. The Judean Peoples’ Front etc are almost more cooperative than the rebels who fought for control of the Temple Mount even as Vespasian built his siege ramps.

@3: Yes! That’s how you know there are no more encores :(

“Romani ite domum”. I first came across this film when my school’s chaplain showed it to us in our religious education class, as a starting point for a discussion around personal vs organised religion. The Latin lesson struck a chord with us.

Brilliant essay, thanks.

@15 – what, you mean they didn’t show it open air in the big stage area in the Town Square across the street from the beach? The nerve of them.

P.s. Cute town – I visited it in February. You can see it yourself if you watch The Truman Show.

@14: “Let them learn Latin as an honor, and Greek as a treat” (Churchill). Given the Pythons’ educations, I expect at least some of them knew of the split but thought that viewers wouldn’t; Romans==Latin is simple, and I’d guess that viewers would be more likely to remember Latin suffixes than Greek, if only from mottoes etc rather than study. (Wikipedia says the Latin drill was from life — Cleese had taught Latin while waiting for a college slot to open up.)

Robert Sellers’s Very Naughty Boys tells the story of the life and death of Handmade Films. I haven’t seen verification of whether Denis O’Brien was really the horrible person the book presents, but there’s lots of fascinating material about the process of choosing and making the various movies; ISTM that as movie studios go they had a better than average ratio of good movies to bad.

Great essay about my favorite Python movie.! I

@9 – Greek was the lingua franca, but the Romans themselves spoke Latin on a day to day basis. The majority of Romans present in Judea in the 1st century would have been Roman administrators and the men of the 10th Legion; while the administrators would have spoken Greek as well as Latin, the legionaries would mostly have spoken Latin with maybe a smattering of basic Greek and Aramaic for communicating with the locals.

If you’re telling an occupying army to piss off, you do it in their own language, not whatever happens to be the lingua franca in use in that time and at that place.

And, the egregious error in the “lesson” notwithstanding, a far, far higher proportion of the audience will have got the joke (specific schoolboy Latin errors) than would have got the same joke using Greek, especially as by the time a person starts learning Greek they’re normally past the schoolboy Latin errors so they don’t arise again in Greek (where the rules re cases for motion towards etc are similar but not identical).

@24/Muswell: Okay, interesting to know. Except I thought that the Romans recruited soldiers from all over the Empire, then shipped them far from home so they’d have no local allegiances. So I’d think that would make the language thing a tossup where the soldiers are concerned. Maybe they learned Latin when they were recruited and trained, but it wouldn’t be their native language any more than Greek.

And I’m not suggesting the Pythons should’ve written the scene to use Greek; I’m just addressing Leah’s comment about the historical accuracy of the film and wondering if that includes the language lesson scene. Obviously one can excuse artistic license for the sake of comedy. I doubt there were any flying saucers abducting random Judeans in Biblical times, and I doubt there were a lot of singalongs on Golgotha.

@25 – Yes, the Romans recruited from all over the Empire and shipped the soldiers off to places where they weren’t local, but those soldiers were Auxiliaries, not Legionaries. Legionaries were Roman citizens. In later years as provincials were more likely to have citizenship there would be provincials serving in the Legions rather than just the Auxiliaries, but in the early first century that would have been very, very rare and the vast majority of Legionaries were from in or near Rome itself and native Latin speakers.

@26/Muswell: Ah, okay. Makes sense that the higher-ranked ones would be from the ruling culture.

Life of Brian being one of my favorite movies, I bought the DVD, and have enjoyed watching it many times. Blessed are the cheesemakers.

Terry Jones’ degree was in history, he was as I understand it a decent medaevalist, he certainly did a series on the period for, I think, the BBC. Anyway he may well have felt that they might as well get the history correct as not, and swung it with the rest of the Pythons.

I find the discussion with Mervyn Stockwood and Malcolm Muggeridge painful because of the absolute arrogance it shows, an arrogance that in far too many ways still persists in a section of our ruling classes, see the whole “one rule for them” Partygate Scandal debacle for a current example.

I saw the film when it came out, and, having been raised a Christian, was amazed at the ignorance behind the protests: the film takes Jesus absolutely seriously.

“Brian … does not have a seat at Anyone’s right hand awaiting him.”

Nope. Brian shows throughout the film that he deserves what Jesus said to the criminal crucified with him: “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise.”

@30/Msb: I’m reminded of when Xena: Warrior Princess did a 4-part arc set in India and dealing with Indian mythology. Hindus objected to the episode that depicted Krishna as an onscreen character, but in my opinion, that was the least objectionable of the four episodes, the one that treated Hindu myth and culture with the most accuracy and respect rather than resorting to negative stereotypes and misinterpretations.

Anyway, speaking as a secular humanist, I’ve long been of the opinion that the real, historical Jesus’s life may have been a lot closer to Brian’s story than the Bible would have it. I figure he was just a good, compassionate guy who preached kindness and understanding for others and freedom for his people, and got blown up into a Messiah figure by the people around him, whether he wanted it or not. I think he would’ve been too humble to want people to make it about him rather than about the message.

@31 / Christopher

If you’ve never read the Gospels, your assumption of Jesus “was just a good, compassionate guy who preached kindness and understanding for others and freedom for his people, and got blown up into a Messiah figure”.

But. To sum the rest of my point, this is clearly not true if you read the Gospels (*Everyone* had a strong opinion about Jesus, good or bad, & he literaaly flipped tables & verbally sparred w/ religious leaders.)

Also, Jesus’s followers didn’t embelish his story. The Gospels are eye witness accounts written remarkably close to after Jesus died & (to all evidence) rose again. They are also not the only historic evidence. The writers of the gospels also make it clear how they are astonished to find the tomb empty, for example & related embarrasing things they say & do.

If you read the Gospels, it’s clear Jesus was an active, dynamic man who caused a stir everywhere he went.

He often talked about how he is actually God, & talks to God, & mentions his own death & the end of the world.

As C S.Lewis put it, either Jesus was mad or he actually was God.

Let’s stay on topic and keep the discussion directly related to the movie and the points made in the original article above–there are any number of possible personal and theological interpretations and beliefs about the historical nature/reality of Jesus, but that’s a different conversation; this is a discussion about The Life of Brian, its release, and its message. Thanks!

As regards the Latin lesson, the specific technique of grabbing the pupil by the ear and twisting it, while shouting at them to declaim bellum, was used on my by my Latin teacher, and this was in the 1990’s! The Latin teach himself though had been teaching since the 1950’s, and very much embodied the same teaching principals the Pythons might have endured.

I’ve no idea how grabbing my ear was supposed to help me, but then I dropped out after a year :)